By Kasey Cain, California H&V

Nothing went according to plan with my oldest son’s birth. He was sunny-side up and his heart rate dropped seven times in labor. After many attempts to reposition, I finally had a C-section. He didn’t pass his first hearing screening but was very difficult to soothe. On day two, he “eventually” passed in his left ear, but not his right. “It’s probably fluid or maybe vernix in his ears since he was born through C-section,” we were told. We dutifully showed up to get his “pass” two weeks later, or so we thought. Zander failed in both ears. We were shocked. Like most families, we had no family history of hearing loss. All fluid should have been gone by now. After the ABR, we learned he had sensorineural hearing loss, mild-moderately severe on his left, and worse on his right. I was speechless when I asked a quiet question over my sleeping newborn and the audiologist answered in her normal tone of voice, “He can’t hear us right now.” What could he hear?

Then came the phone calls before I had shared the news with my own mom. That first message: “Hi, I’m with the County Office of Special Education,” seemed so abrupt to us as rookie parents submerged in caring for a newborn. (Who told you our son has hearing loss and who the heck are you people?) Would our son experience the stigma we saw when we were in school? Will he have friends? Will others make fun of him? Unnerved, we nonetheless blindly walked our way through all of the right steps. Looking back, I know postpartum depression colored my days and I was filled with mom guilt. Could his hearing loss be caused by his difficult labor or the pre-workout chemicals I drank before I knew I was pregnant?

Returning to work at my sales position coincided with his first appointment to get hearing aids at three months. The early intervention angels who (as I called them) had begun with a visit to our house to start services. Group sessions including other parents occurred during the day, but we both worked days, so in the beginning we could only have 1-2 visits a month at the daycare center. I rushed from work to meet them. We cautiously came to the hearing aid appointment but ultimately walked out without hearing aids. It was all too much, and we still felt we didn’t understand what it all meant or knew of the complications that could arise. We didn’t even know the right questions to ask.

Lost in the Middle

For months we made loud noises to try to elicit reactions. Hearing loss is invisible. Was it a real diagnosis? Did he need aids? I could see that he didn’t hear me calling him outside the shower while he played in his baby seat. We went back to audiology at nine months; he was aided the next month. Right away, we saw a night and day difference! Then the chronic ear infections began. Zander would get antibiotics, then tubes, and then another infection. Fluid would even drip down his shirt. He would get his ears suctioned, restrained in a mummy wrap to keep him still (I was pregnant with his baby brother by then) in a procedure that terrorized him. This cycle repeated, stopping his hearing aid use during infections. Progress stalled. A client encouraged me to ask about removing adenoids, but the ENT wanted to stay conservative for now.

All we had for communication was the few signs we knew. We still couldn’t attend the early intervention (EI) groups regularly. Never mind that my background is in media sales, and I had no foundation in language development or understanding the true gravity of what was going on. We had a Deaf mentor who started coming to the house, but there were still big gaps developing. We ended up seeing a pediatrician on call during yet another fluid dripping on his shirt infection, and he agreed right away to an Xray for adenoids. They were inflamed. Could this be the “cure”? (I still didn’t fully understand sensorineural hearing loss at this point.) Soon after surgery, heading out the door with his dad to go to the park, I said “Have fun! Bye, guys!” Zander smiled and said, clear as day, “Bye-bye!” Finally, his first words at 18 months of age!

A Lifeline: FMLA

As he neared 28 months, we wanted to know why his speech was still so delayed. SKI-HI assessments failed to show us the missing piece. I started to ask my work permission to attend EI groups during the day. I still remember hearing the words “language deprivation” and about the critical period for language learning. What I read freaked me out even more. I was desperate to quit my job but I couldn’t; we needed the money. I couldn’t be fully present at the group EI sessions held only during my workday. I panicked. He was nearly three. Since I was 100% commission, I had to step out for calls. My mom told me to ask about intermittent family leave from her years in human resources. Our pediatrician had no problem signing off on that paperwork while I was still in persuasion mode. With my job protected by the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), I could better focus on early intervention, other appointments, and working with Zander.

We also took him out of daycare. My husband would drop him off in the noisy two-year-old room with 24 kids and two adults. No one encouraged him to sit near the teacher at circle time, instead letting him wander off and stare out the window. Despite those visits (weekly at this point) with EI, childcare was not a language-rich place for him. I was thrilled to spend two days focusing on his learning needs.

I didn’t understand what I needed to do. When our EI folks said “you need to sign to your son,” I didn’t truly know what the purpose was or why I should read with him every day. I tried not to compare him to the other kids whose mothers had quit working, they seemed so far ahead. I was trapped in a sense by a good salary, and couldn’t see a way out.

Because of my son’s journey, I felt a calling to get into audiology, mentioning it one day to an educational audiologist at EI. I laughed it off, telling her I’d be 40 before I graduated from the program. She said, “Kasey, that’s still 25 years in a very fulfilling career.” My eye-opening moment: the thought of 30 more years in sales filled me with dread. I met with advisors and was able to finish my bachelor’s degree online on top of taking prerequisites for the doctoral audiology program. I was on the ultimate fast track to change my career.

After six months of intermittent family leave, Zander entered a total communication preschool following his first IEP. A speech pathologist felt he had a language delay only ten minutes after meeting him, outside of hearing loss. We had a few months of progress, then the pandemic shutdown. A three-year-old is not a great fit for online preschool, nor were we equal to the task of teaching him through homework assignments on the Seesaw app while trying to work, raise a newborn, and focus on sales that had disappeared during the lockdown.

A New Diagnosis

When Zander returned to preschool in the spring of 2021, the educational audiologist noted concerns with Zander’s responses. He wasn’t easy to test. EI had recently helped him learn how to drop the block when he heard a sound for Conditioned Play Audiometry in the soundbooth, but he still wasn’t consistent enough. Around his 4th birthday, Zander got a new label: Bilateral EVA or Enlarged Vestibular Aqueducts (EVA), a condition from birth that causes progressive loss. When his educational audiologist mentioned a cochlear implant, I hesitated. Our county is very Deaf Culture-centric, even in early intervention. We couldn’t take away his Deaf identity. Thankfully, a para in his class who was Deaf told me that her husband was also Deaf and used cochlear implants. Zander could have the best of both worlds, too.

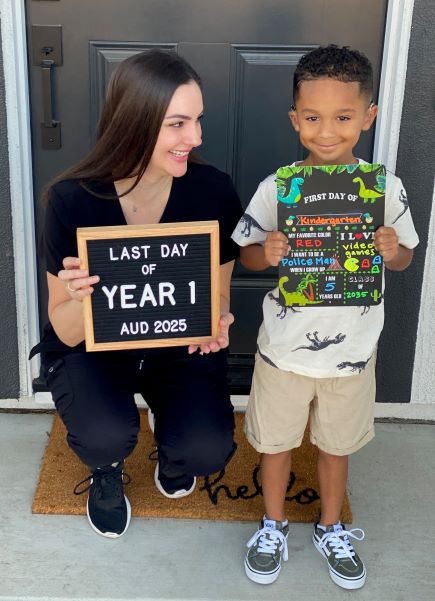

Today, he is thriving in kindergarten with a cochlear implant and hearing aid. The language disability label was removed at his triennial. Knowing what I know now, I can’t help but see what could have or should have happened. At every point, from his multiple screenings, early intervention, and audiology, missed opportunities to prevent his delays occurred. Looking back, when asked how Zander was doing, I would smile and say, “Fine!” I had no idea where he should be and what to ask. Subconsciously, I felt that any issues were a reflection on us. Now, I have a dream of being an audiologist who can sign, who can connect with working parents like me, and do my best to engage parents in these critical early years of language learning.